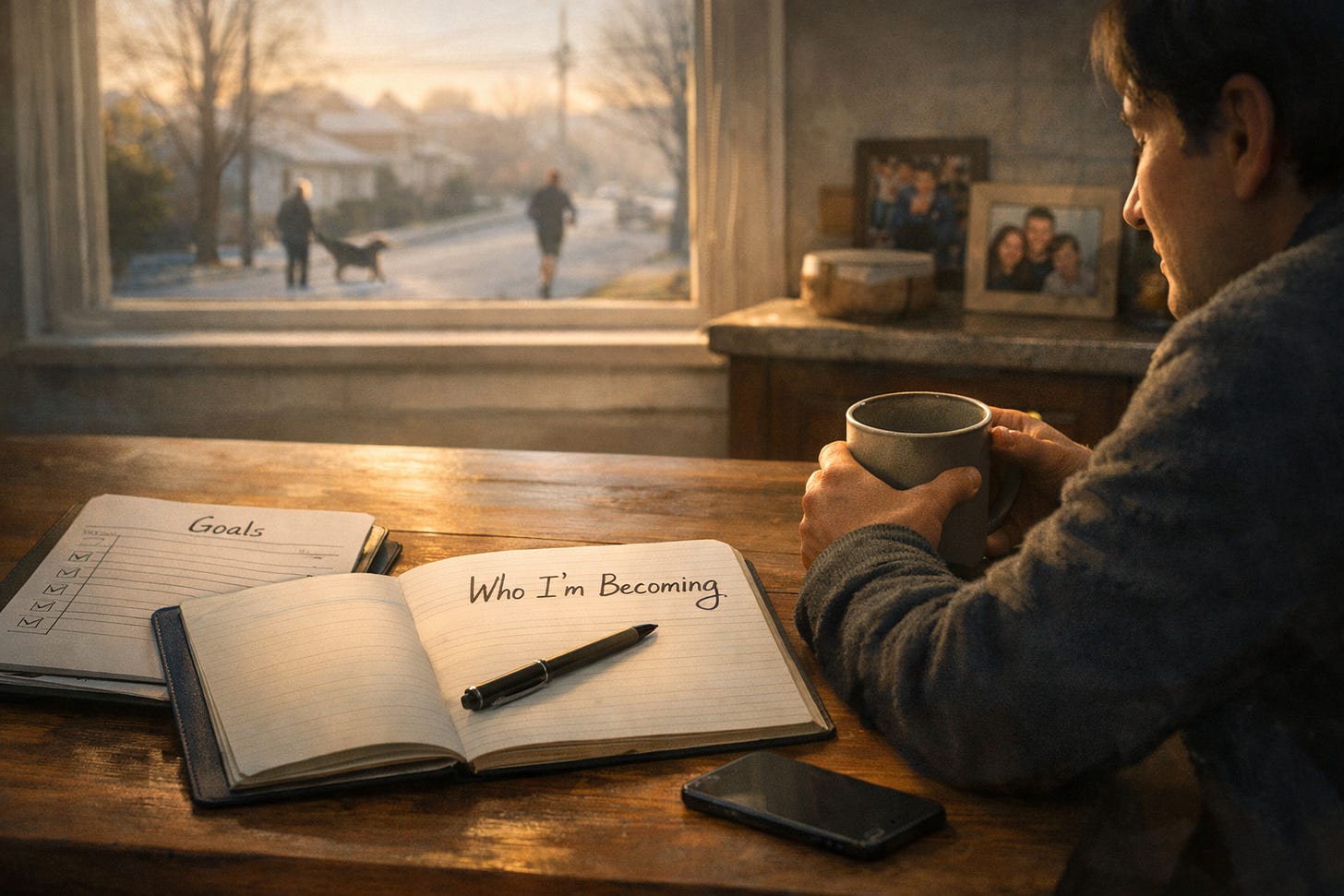

From “What Do You Want to Achieve?” to “Who Are You Becoming?”

It usually starts in a quiet place.

Not the dramatic collapse people joke about in February, when the gym empties out and the new habit apps stop pinging. It starts earlier than that, and softer. A moment you can almost miss.

You are standing in the kitchen, or sitting in the car, or looking at a planner you once believed in. Nothing is exploding. No one is yelling. Life is simply moving along.

And then you notice it: the small, familiar disappointment. The kind that does not demand attention, but quietly settles in your chest like a stone.

You did it again. You started strong, and then you faded. You made promises to yourself, and then you negotiated them down. You said, “This time will be different,” and then time proved, again, that you are not as consistent as you want to be.

If you are honest, what hurts most is not the missed outcome. It is the story that climbs onto the missed outcome like a parasite.

Why can’t I stick with anything?

What is wrong with me?

Why do I always quit?

That is shame, and shame is never content to stay attached to a behavior. Shame wants to become identity.

This is why so many goals fail in a way that feels personal. A goal is supposed to be a tool. Instead, it becomes a verdict.

Identity-first living is the move that interrupts that verdict.

Not by throwing goals away. Goals are often useful. They can create clarity, boundaries, and direction. But they are downstream. They are not the engine of change. They are the output of something deeper.

And what is deeper is this: the person you believe yourself to be, the person you are becoming, and the kinds of actions that feel natural for that person.

Reframing the question

Most people have been trained to ask the same question each year: What do you want to accomplish?

It is a reasonable question. It is just too small to carry the weight we put on it.

A better question, especially for thoughtful adults who are tired of the churn, is less performative and more formative: Who do you want to become in this season of life?

That question does not reject outcomes. It simply relocates them. Outcomes become indicators rather than identity. They become instruments rather than masters.

And because this is a human question, not a corporate question, it naturally brings the conversation back to what goals often ignore: the inner life, the long story, the kind of person your life is shaping you into when no one is watching.

The three layers of change

When people say they want change, they often mean one thing, but they are actually dealing with three.

At the surface are outcomes, the results we can measure. Lose twenty pounds. Finish the manuscript. Pay off the credit card. Grow the business. Get the promotion. Outcomes matter, but they have a built-in weakness: you cannot live inside them. You cannot do an outcome on a Tuesday night when you are tired.

Under outcomes are processes, the repeatable behaviors that create outcomes. Walk after dinner. Write three hundred words. Review the budget every Friday. Turn the phone off at 9:30 p.m. Processes are where life actually happens, but processes have their own weakness: they collapse when they are fueled only by pressure, guilt, or a temporary surge of motivation.

Under processes is the deepest layer: identity, the self-concept you carry, the story you believe about who you are. This is the layer that quietly decides which processes will feel like “me,” and which will feel like a costume you will eventually stop wearing.

This is why identity-first living is not motivational fluff. It is a more accurate model of what people actually do.

We drift toward behaviors that fit the person we believe ourselves to be. And we resist behaviors that feel foreign to that person, even when we want the results those behaviors produce. Researchers who study habits have repeatedly shown how much of daily life is guided by repetition in stable contexts, with cues in our environment pulling us toward familiar actions before we have time to think ourselves into something better.¹

In other words, you can have strong intentions and still find yourself living out an older identity, reinforced by old cues, in old places, at old times.

Identity-based motivation in plain language

Here is the simplest way to say it.

People tend to act in ways that feel consistent with “who I am.”

Not who they wish they were in the abstract. Who they believe they are, right now, in their bones.

If you have ever said, “I’m just not a morning person,” or “I’m not disciplined,” or “I’m terrible with money,” you have felt the gravity of identity. Those sentences are not merely descriptions. They are permissions. They quietly shape what you attempt and what you tolerate.

And that is why shame is so destructive. Shame takes a temporary pattern and tries to make it permanent. It does not say, “This plan failed.” It says, “You fail.”

Identity-first living does not answer shame with hype. It answers shame with a deeper truth: identity is not only inherited; it is constructed. Not instantly. Not magically. Constructed through repeated, small evidence that begins to rewrite what you believe is possible for you.

Why identity feels deeper than goals

Identity feels deeper than goals because it is tied to the parts of you that goals often leave untouched.

It is tied to self-concept, how you interpret your own behavior. When you miss a goal, you do not merely miss a target. You interpret the miss. You assign meaning to it. And if your default interpretation is shame, the miss becomes a message about who you are.

It is tied to story, the narrative you are living inside. Psychologist Dan McAdams and others have argued that many adults make sense of their lives through an internalized life story, an evolving narrative that integrates the remembered past and imagined future and gives a sense of unity and purpose.² When your goals are disconnected from your story, they are fragile. They cannot carry fatigue, stress, disappointment, or slow progress. They feel like obligations rather than expressions of who you are becoming.

And identity is tied to meaning, which outlasts motivation. Outcomes can motivate, but meaning sustains. If the only “why” is an external metric, effort becomes brittle. But when the “why” is identity, effort becomes alignment. You are not merely chasing a result. You are practicing a way of being.

This is also why identity-first living does not treat goals as enemies. It simply assigns them their proper role. Goals become downstream from identity, serving it the way a map serves a traveler.

The cost of ignoring identity

When identity is ignored, two painful outcomes are common.

First, you can achieve things that do not change you. You can hit the number, reach the milestone, and still feel the same internal instability that made the journey exhausting. The achievement lands on top of an unchanged self, and then the fear begins: can I keep this up, can I maintain it, what happens when life gets hard?

Second, you can succeed and still feel misaligned. The goal was achieved, but it did not fit the person you actually want to become. In that case, the emptiness is not because success is meaningless. It is because success was asked to do an impossible job. It was asked to deliver identity.

A goal cannot carry that weight.

How identity becomes practical: if–then plans and environment design

The question, then, is how identity stops being a nice idea and becomes a lived reality.

Two research-backed concepts help make the bridge: implementation intentions and environment design.

Implementation intentions are simple “if–then” plans that connect a predictable situation to a specific action. Research syntheses and meta-analyses associated with Peter Gollwitzer and colleagues suggest that these plans help close the gap between intention and action because they pre-decide what you will do when a certain moment arrives.³ The point is not sophistication. The point is clarity.

If identity is the foundation, an if–then plan becomes an identity enactment.

You are no longer hoping you will do the right thing when you are tired. You have already decided what a person like you does when the moment comes.

Environment design is the companion truth that keeps you from moralizing every lapse. If habits are strongly cued by recurring contexts, then changing the environment is not cheating. It is wisdom. Wendy Wood’s work emphasizes how repeated behaviors become associated with context cues, and how those cues can trigger behavior automatically.¹ If you keep asking yourself to win a daily fight against an environment that is constantly cueing the wrong behavior, you will eventually interpret fatigue as failure. Identity-first living is gentler and smarter: it changes the cues so the desired behavior becomes the default.

Put differently, the question is not only “Do I have enough willpower?” The question is “What does my life repeatedly cue?”

Case examples (same goal, different identity foundation)

Health: “I want to lose 20 pounds.”

Version 1: Goal-first, identity-shame underneath

The goal is clear. The plan is intense. The early results feel like relief. Then a disruption arrives, travel, stress, a tough week, a few off-meals, and the slip becomes a story: “I knew I would fail.” The process collapses not only because the plan was too strict, but because the identity underneath it was already fragile.

Version 2: Identity-first, goals downstream

The goal exists, but it sits under a larger identity: “I am becoming a steady, healthy person.” The plan is smaller and repeatable. There is an if–then structure: “If dinner is done, then I walk for fifteen minutes.” The environment shifts: the default foods at home fit the identity, and the cues that trigger mindless eating are removed or made harder. Progress is slower, but shame loses its grip because lapses are treated as data, not verdicts.

Leadership: “I want to be more productive and respected.”

Version 1: Productivity as self-worth

The goal becomes a proxy for identity. Busyness becomes proof of value. The person is always available. Work expands to fill every space. Respect may increase for a season, but peace disappears. Eventually the leader becomes reactive, brittle, and resentful.

Version 2: Identity-first leadership

The identity is not “I am a productive person.” It is “I am becoming a clear, calm, steady leader.” The goal of productivity remains, but it is reframed: productivity is what serves clarity and faithfulness, not what earns worth. The if–then plan is relational and strategic: “If a new request arrives, then I clarify priority before I commit.” The environment shifts: notifications are reduced, meeting rhythms are structured, and focus time is protected. The result is less drama, more trust, and a kind of respect that is rooted in steadiness rather than frantic output.

A single identity with evidence markers

Because shame is the dominant pain for many readers, the practical next step must be simple enough to survive real life.

The next article will focus on naming one unifying identity for the season, then choosing a small set of “evidence markers,” repeatable behaviors that serve as proof, not performance.

For now, it is enough to notice the shift.

If you have been living under the question, “What do I want to achieve?” you may be stuck in a cycle where every missed outcome becomes an indictment.

Identity-first living offers a truer question:

Who am I becoming, and what small evidence will I practice this week that supports that becoming?

That question does not eliminate goals. It redeems them. It puts them where they belong, downstream from identity, serving the deeper work of becoming.

Footnotes

Wendy Wood, “Psychology of Habit,” Annual Review of Psychology 67 (2016): 289–314; Wendy Wood, “Healthy Through Habit: Interventions for Initiating and Maintaining Health Behavior Change,” Behavioral Science & Policy 3, no. 2 (2017): 71–83.

Dan P. McAdams, “The Psychology of Life Stories,” Review of General Psychology 5, no. 2 (2001): 100–122; Dan P. McAdams, “First We Invented Stories, Then They Changed Us,” (2019) (essay summarizing narrative identity as providing unity and purpose over time).

Peter M. Gollwitzer and Paschal Sheeran, “Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of Effects and Processes,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38 (2006): 69–119; Frank Wieber et al., “Promoting the Translation of Intentions into Action by Implementation Intentions,” (2015) (review discussion of effects and mechanisms).