Leaving a Light On: Staying Awake for Jesus’ Coming

Exegesis of Matthew 24:36–44, Advent Week 1, 2025

Matthew places this passage inside the Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24–25), Jesus’ final extended teaching before the Passion narrative. It is delivered on the Mount of Olives, with the Temple in full view, after Jesus has pronounced woes upon the scribes and Pharisees and predicted the Temple’s destruction. The disciples have asked, “When will this happen, and what will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?” (24:3, NIV). Matthew 24–25 is Jesus’ answer.

By the time we reach verses 36–44, Jesus has already described upheavals—wars, earthquakes, persecution—and has warned about false messiahs and the desecration of the holy place. The focus now narrows from “signs” to uncertainty of timing and the necessity of watchfulness. The paragraph serves as a hinge between apocalyptic description and the parables of faithful/unfaithful servants that follow.

The key opening statement is stark: “However, no one knows the day or hour when these things will happen, not even the angels in heaven or the Son himself. Only the Father knows” (24:36, NLT). Some manuscripts omit “nor the Son,” likely because scribes were uncomfortable with the idea that Jesus did not know, but the more difficult reading is almost certainly original and is widely accepted in modern critical editions (Sermon Writer).

Jesus then invokes the “days of Noah” as a pattern. People were eating, drinking, marrying—living ordinary lives—until the flood came and “swept them all away” (24:39). In the same way, the coming (parousia) of the Son of Man will arrive amid normal routines. Two men in a field; two women grinding at a mill; one is “taken,” the other “left” (24:40–41). The point is not speculation about a secret rapture but the sudden, divisive effect of the Son of Man’s coming on people who appear indistinguishable from the outside.

The passage ends with the image of a homeowner who would have stayed awake if he had known the hour a thief was coming. Jesus’ command is simple and repeated: “Keep watch” (24:42) and “You also must be ready” (24:44). This section is therefore best read as a summons to vigilant, ethical readiness in the shadow of coming judgment and the promised restoration of all things, rather than as a code to crack the calendar of the end (Working Preacher).

We are speaking into a late-modern, digitally saturated congregation heading into Advent. Many are exhausted by constant alerts about climate, elections, wars, AI, and economic instability. Their “watchfulness” is often not spiritual attentiveness but anxious doom-scrolling. They know what it is to live with a low hum of dread in the background.

Within the church, responses diverge:

Some avoid apocalyptic texts; they associate Matthew 24 with charts, arguments, or fear-based preaching from their past. They have quietly filed “end times” under “embarrassing or irrelevant.”

Others have absorbed a pop-culture eschatology—movies, novels, social media clips. For them, “one taken, one left” evokes rapture imagery more than covenantal hope or ethical urgency.

A growing number are simply numb. Between family pressures, economic strain, and chronic news fatigue, they feel they are already living in a kind of permanent emergency. The command “stay awake” might sound like a curse, not a gift, in a world where insomnia and burnout are rampant.

At the same time, Advent opens a door. Even secular culture knows something about waiting in the dark—string lights in early sunsets, candles in windows, the ache of absent loved ones. Many in the congregation carry a private longing: Is there a story bigger than the headlines? Is anyone actually coming?

The sermon therefore needs to:

De-weaponize apocalyptic language (away from fear-mongering and speculation).

Re-frame “watchfulness” as trustful attentiveness rather than anxiety.

Show that Jesus’ “unknown day and hour” is not a threat but a call to live fully awake to grace now.

Offer concrete practices of awake discipleship in ordinary life—fields, mills, offices, kitchen tables.

Exegetical Exploration

24:36 – “But concerning that day and hour no one knows…”

Greek: Perì dè tēs hēmeras ekeinēs kai hōras oudeis oiden, oude hoi angeloi tōn ouranōn [oude ho huios], ei mē ho patēr monos (BibleGateway).

The verb oiden (a perfect of oida) is the standard verb in this passage for “knowing.” It appears again in v.42 (“you do not know on what day your Lord is coming”). Exegetes note that oida can suggest a kind of settled, comprehensive knowledge, but here the emphasis is on its absence: the timing of “that day” is comprehensively hidden from every creaturely perspective (The Acedic Lutheran).

The phrase “nor the Son” (present in many early witnesses) underscores the functional self-limitation of the incarnate Christ. As France observes, there is a paradox that the very Son who will preside over that day does not, in his incarnate state, hold its timetable (Ministry Magazine). This protects the mystery of God’s sovereignty and rebukes human attempts to secure what has not been given.

24:37–39 – “As it was in the days of Noah…”

The comparison with Noah focuses not on spectacular wickedness but on ordinary preoccupation: “eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage” until the day Noah entered the ark (v.38). The problem is not that these activities are sinful; they are normal. The issue is blindness to the deeper reality of God’s patience and coming judgment.

Verse 39: “They knew nothing (ouk egnōsan) until the flood came and swept them all away.” Here Matthew shifts to ginōskō (“they did not come to realize”), describing the tragic recognition that arrives too late. The same verb pair (oida / ginōskō) hints at a contrast: disciples are told they do not know the timing but do know the certainty and character of the Son of Man’s coming. The generation of Noah refused that knowledge (The Acedic Lutheran)

The flood “took them all away” (ēren hapantas). In context, the ones “taken” by the flood are the unprepared; Noah is left alive, preserved by obedience. This matters for reading vv.40–41.

24:40–41 – “One will be taken and one left”

“Then two men will be in the field; one will be taken (paralambanetai), and one left (aphietai). Two women will be grinding at the mill; one will be taken and one left” (NRSV). The verbs differ from v.39, and interpreters debate the direction: Is “taken” salvation (taken by Christ) or judgment (as in the flood)?

Because the immediate analogy is “swept away” in judgment (v.39), there is a strong case that “taken” in vv.40–41 continues that note: sudden removal in judgment, with “left” implying preservation. Others see “taken” positively, aligning with passages where Jesus “takes along” disciples as companions. The ambiguity is likely intentional; what matters is the sudden, divisive disclosure of people’s true stance toward the Son of Man within apparently identical daily work.

Either way, the focus is not on mapping secret transport logistics but on the impossibility of last-minute scrambling. In the moment of revelation, people are found to have been living either heedfully or heedlessly all along.

24:42–44 – “Keep awake… be ready”

“Keep awake” (grēgoreite) is a key verb in Matthew’s Passion narrative as well (26:38–41). Jesus urges the disciples to stay awake with him in Gethsemane, and they fail. Watchfulness is not mainly about scanning the horizon for signs but about sharing the vigilance of Jesus in prayer and obedience.

The parable of the householder and thief (vv.43–44) uses a negative image: a homeowner would stay awake if he knew the hour of attempted burglary. The implication is that disciples must cultivate that same seriousness in reverse: not fearful suspicion but a steady awareness that the Lord may come at any time. Paul and other New Testament writers pick up the “thief in the night” motif in similar ways (1 Thess 5:2–6; 2 Pet 3:10) (Wikipedia).

The verse 44 summary is programmatic: “Therefore you also must be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an unexpected hour” (NRSV). Read within Matthew 24–25, “ready” is defined not as stockpiling information but as embodying faithful stewardship, mercy, and active love (see the following parables and the judgment of the nations in 25:31–46) (Religion Online).

Several key symbols structure the passage:

The Unknown Day and Hour

The hidden timetable is a sign that the future is not an object we can control. It resists commercialization and prediction. In semiotic terms, “unknown” marks the boundary between creaturely planning and divine freedom. The refusal of a disclosed schedule forces disciples to relate to a Person (the Father, the Son), not to a prophecy chart.The Days of Noah – “Business as Usual”

Noah’s generation is not pictured in lurid sin but in ordinary life. The symbol here is routine—weddings, meals, work. Routine becomes dangerous when it blinds us to urgent realities, like villagers ignoring tsunami stones that warn, “Do not build any homes below this point,” ancient markers that helped some Japanese communities survive later tsunamis by remembering older warnings (Wikipedia)Two in the Field, Two at the Mill

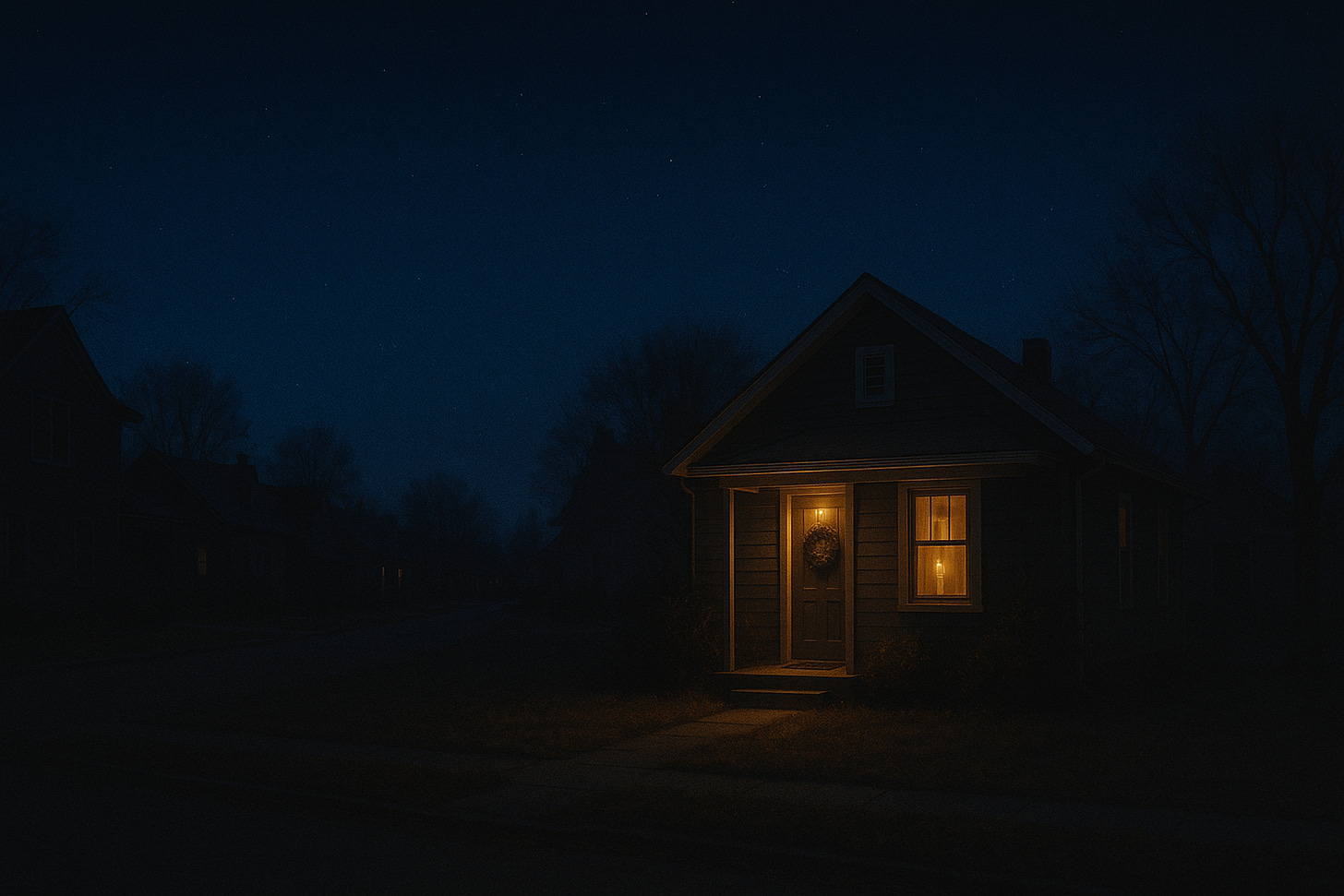

These paired images signal how judgment and salvation cut across social sameness. The field and the mill are places of economic collaboration and gendered work in the ancient world. Semiotic weight: outward similarity does not reveal inward orientation. This pushes against cultural Christianities where church belonging, political affiliation, or family tradition are mistaken for watchful discipleship.The Thief in the Night / The House at Night

The thief symbol communicates sudden, disruptive arrival. A dark house with a drowsy homeowner becomes a sign for spiritual sedation—a life where distractions have replaced vigilance. Modern parallels include regulations like the “sterile cockpit rule,” which forbids non-essential conversation below 10,000 feet so pilots can focus when the margin for error is small (ASRS).Wakefulness vs. Sleep

“Keep awake” functions not only as metaphor for cognitive alertness but as invitation to participatory attentiveness—prayer, mercy, justice, hospitality. In a world drowning in notifications, Jesus’ wakefulness is qualitatively different: not frantic hyper-vigilance but steady love.

The central symbolic cluster, then, is a household in the dark: routine continuing, lights perhaps on, but souls half-asleep. Into that house Jesus speaks: leave a lamp on, stay awake in love, because the Lord may come at any moment—into your schedule, your neighborhood, your systems of power.

Image-Driven Big Idea

In a world lulled by “business as usual,” Jesus calls his people to live like a home that keeps a light on in the night—awake, hospitable, and ready for his quiet arrival.

Three supporting theological movements:

The Unknown Hour Protects Grace, Not Fear

The Father’s secrecy about “day and hour” is not divine teasing. It prevents the reduction of discipleship to deadline management. If we knew the date, we would cram. Not knowing means that every day is potentially Advent Eve; every act of love is lived under the open sky of Christ’s promised return.Ordinary Life is the Arena of Readiness

Jesus locates watchfulness in fields and mills, not monasteries. Readiness is not withdrawal from normal responsibilities but carrying them out in a posture of responsive obedience—honesty in spreadsheets, gentleness with children, integrity in contracts. The Son of Man comes to people at work, in kitchens, on commutes.Watchfulness is Ethical, Not Merely Cognitive

The following parables make clear that “staying awake” is expressed in mercy, stewardship, and care for “the least of these.” True eschatology is always ethical. The church does not “watch” by hoarding information but by living now the kind of life that will make sense when Jesus appears: cross-shaped love.