Supply Chains Rewritten: How Global Businesses Are Redrawing the Map of Trust

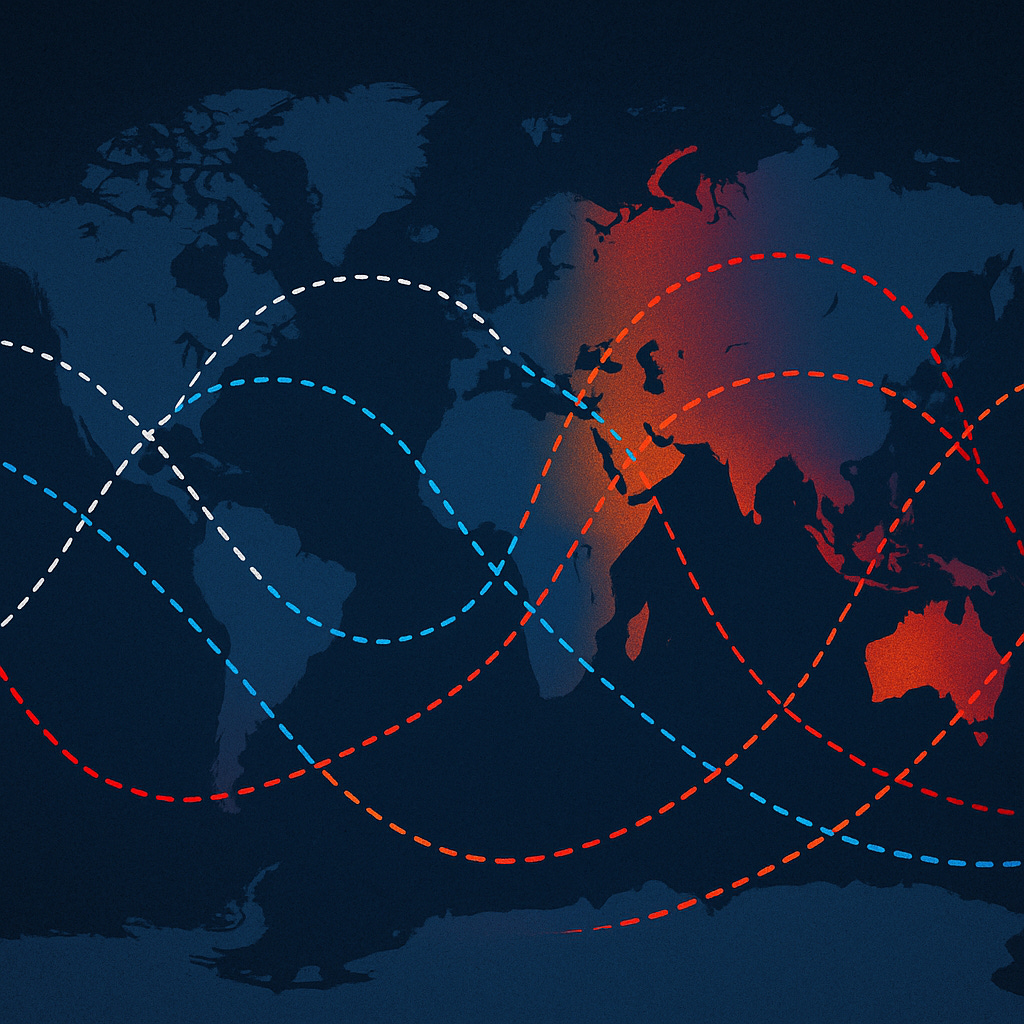

Midnight at a major port, cranes move in slow arcs, but the rhythm has changed. Containers once stacked for a direct line across the Pacific now pause in new waypoints. Some swing toward Haiphong instead of Shenzhen, others route to Manzanillo instead of Long Beach, others move quietly toward Tangier, Lagos, Mombasa. The choreography feels subtle at ground level. Yet from the vantage point of a boardroom map, the pattern is clear. Companies are redrawing the arteries of global commerce to avoid tariff crossfire, sanctions risk, and the possibility that one political speech can freeze a critical component.

This is not de-globalization. The ships still sail, the data still moves, the orders still flow. According to DHL’s Global Connectedness Tracker, trade’s share of world output in 2023 remained near historic highs and global flows held steady through mid 2024 (DHL Group). But the logic of where goods are made, and under whose shadow, is shifting. Leaders are discovering that supply chains are not neutral plumbing. They are choices about trust, exposure, and whose crisis becomes your own.

The reconfiguration of supply networks is often narrated as a technical story: tariffs, labor costs, lead times, shipping lanes. In reality it is a story about how power and fear shape the everyday systems that feed, wire, and equip societies.

Three forces have converged.

First, geo-economic fragmentation. Trade conflicts, strategic export controls, secondary sanctions, and industrial policy regimes in the United States, European Union, and China have made concentration on a single country or bloc a structural risk, not only an efficiency play. IMF analysis highlights how rising geopolitical tensions and industrial policies have accelerated talk and practice of re-shoring, friend shoring, and near-shoring in sensitive sectors such as semiconductors and clean tech (The World Bank Docs).

Second, regulatory unpredictability. When leaders know that a tariff decision, sanctions package, or local rule change can reprice an entire category overnight, they seek jurisdictions where rules are clearer, contracts are honored, and political motives are legible. Connector economies that appear legally predictable and geopolitically less entangled gain an advantage.

Third, moral visibility. Consumers and investors now pay closer attention to forced labor, environmental harm, and exploitative practices. Supply chains are becoming part of a brand’s conscience. Where you source is no longer a back-office detail. Boards and executives treat exposure to autocratic leverage or human rights scrutiny as both ethical and financial risk.

For leadership, the signal is blunt. The age of single-threaded dependence is over. What emerges is not self-sufficient isolation but a more curated interdependence: portfolios of locations aligned with values, resilience thresholds, and strategic alliances.

The governing principle

Supply chains are moving from the pursuit of cheapest concentration to the design of intentional redundancy inside trusted circles.

This is not a clean break with globalization. DHL’s Global Connectedness Report shows that global flows remain resilient and geographically extended, while also recording a rising share of world trade captured by “connector” economies such as Mexico, Viet Nam, India, Brazil, and the UAE between 2016 and 2024v(DHL Group), The same data set notes that regionalization has not replaced globalization, but diversification within and across regions has accelerated.

For leaders, the logic is:

Reduce single-country exposure where tariffs, sanctions, or political coercion are plausible.

Diversify sourcing toward multiple hubs that are either geographically closer, geopolitically aligned, or legally predictable.

Treat each location choice as a signal of whose risks, norms, and futures you tie to your own.

Leadership becomes an exercise in system curation. You are not only buying components. You are selecting which governments, labor regimes, and alliances sit inside your operational perimeter.

Consider a global electronics manufacturer that once relied on a heavily China-centric model for components and final assembly. After successive tariff rounds, export controls, and shipping volatility, the leadership team redraws its map.

In Southeast Asia, they shift a share of assembly to Viet Nam and Malaysia. World Bank and IMF analyses describe these economies as key beneficiaries of trade diversion, attracting greenfield projects in electronics, textiles, and machinery as firms seek proximity to Asian markets without full exposure to U.S.–China tensions (DHL Group). Viet Nam, in particular, has seen sustained growth in export oriented FDI tied to electronics. The company does not abandon China. It reduces concentration, building parallel capacities in states where trade agreements, demographic depth, and moderate political risk support long term operations.

In Mexico, the same firm establishes a major facility serving the U.S. market. Near-shoring aligns production with USMCA rules of origin, shortens lead times, trims logistics emissions, and lowers tariff uncertainty. Data from DHL’s connectedness work and multiple FDI trackers highlight Mexico’s rising share of global and U.S. bound manufacturing investments, precisely as firms look for “friend shoring” locations that sit inside trusted trade frameworks (DHL Group). Leadership now treats the U.S.–Mexico industrial corridor as a strategic backbone, not an optional hedge.

In Africa, the company experiments. It sources components from Morocco’s automotive and electronics clusters, and pilots partnerships in Kenya or Rwanda for specialized assembly and support services. World Bank regional outlooks point to targeted gains in countries that improve infrastructure and regulatory clarity, positioning themselves as connectors rather than arenas of extraction (The World Bank Docs). The firm’s African presence is still small, yet symbolically important. Executives are not chasing only low wages. They are betting on future markets, diversified political alignment, and the long run value of being present in multiple growth centers.

In each move, the map becomes less elegant, more complex, but more honest. Instead of one fragile line, leaders learn to live with a web of strong-enough ties.

Beneath the spreadsheets, this shift is also a language change.

For two decades, the dominant symbol of supply chains was scale. Mega factories. Mega ports. Mega dependencies rationalized by efficiency stories. Leaders read global maps as proofs of mastery.

The rewiring of networks replaces that symbol with another: alignment.

When a company relocates assembly from a high tension jurisdiction to a treaty bound neighbor, it sends a signal that political compatibility matters as much as wage arbitrage. When flows bend toward Mexico, Viet Nam, or selected African hubs, they encode criteria such as legal reliability, alliance structure, and long term governability. DHL’s findings, showing the growing role of “connecting economies” and stable overall globalization levels, reinforce the sense that the contest is not open vs closed, but about where trust can be operationalized (DHL Group).

Leadership narratives inside firms are shifting with this. The old story: “We go wherever costs are lowest.” The emerging story: “We go where we can keep serving in a crisis without being drafted into someone else’s conflict.”

There is also a moral symbol at work. Friend shoring and near-shoring are not automatically virtuous. IMF research warns that fragmentation and bloc based FDI can harm vulnerable economies and reduce diversification, even as they strengthen some alliances (imf.org). Leaders who treat relocation purely as a political loyalty test risk reinforcing exclusion, cutting off regions from technology and capital, and deepening inequality.

So the semiotic question for leadership is sharp: Are you designing your supply network as a bunker, a weapon, or a covenant.

Bunkers hoard production within narrow circles, accept higher costs, and signal fear. Weapons use sourcing to punish or corner counterparts. Covenants pursue resilience and alignment while preserving openness, investing in partners’ capacity, transparency, and welfare.

The same distribution center layout, the same multi country network chart, can represent any of these three meanings. The data does not decide the symbol. Leadership does.

Application

Four principles for leaders who want to redesign supply chains with strategic and moral clarity:

Diversify on purpose, not in panic.

Set explicit exposure thresholds for any single country or corridor tied to tariff hikes, sanctions, or conflict scenarios. Use DHL style connectivity and IMF / World Bank risk assessments as reference, not folklore. Where exposure exceeds thresholds, phase in alternative sites over time instead of announcing abrupt exits that destabilize workers and partners.

Choose “connector” economies with mutual responsibility.

When investing in Mexico, Southeast Asia, or African hubs, treat them as long term partners. Negotiate on wages and incentives, but commit to skills transfer, local supplier development, and environmental standards. Your presence should expand their strategic options, not trap them in dependency. This converts friend shoring from a bloc tactic into a shared development strategy.

Make ethics an operating constraint, not a press release.

Embed labor rights, rule of law, and transparency criteria into vendor and location selection. If a jurisdiction penalizes dissent, uses forced labor, or weaponizes interdependence, treat that as baseline risk, regardless of its margins. Document the tradeoffs for your board. Silence is also a signal.

Align internal governance with external exposure.

Supply chains rewritten on paper mean little without matching decision processes. Establish cross functional risk councils that include operations, legal, security, finance, and sustainability. Review network structure quarterly against geopolitical and regulatory changes, using verifiable indicators, not headlines. Tie executive incentives in part to resilience metrics: time to reroute, share of multi sourced inputs, share of spend in compliant and stable jurisdictions.

The map of trade will continue to move. New crises will flare. New ports will rise. Leaders do not control those tides.

They do control where they anchor.

Supply chains are being rewritten in quiet transactions and revised contracts, but they are also written in the character of those who lead them. To design networks that outlast the next tariff cycle, leaders will need more than clever logistics. They will need the courage to choose partners they trust, the patience to invest where they land, and the humility to remember that every route they draw links human lives, not only unit costs.

If the next decade belongs to those who de-risk with wisdom instead of fear, then the work begins with a hard question in every boardroom:

What story does our supply chain tell about who we stand with, and who we refuse to abandon, when the world grows unsteady.