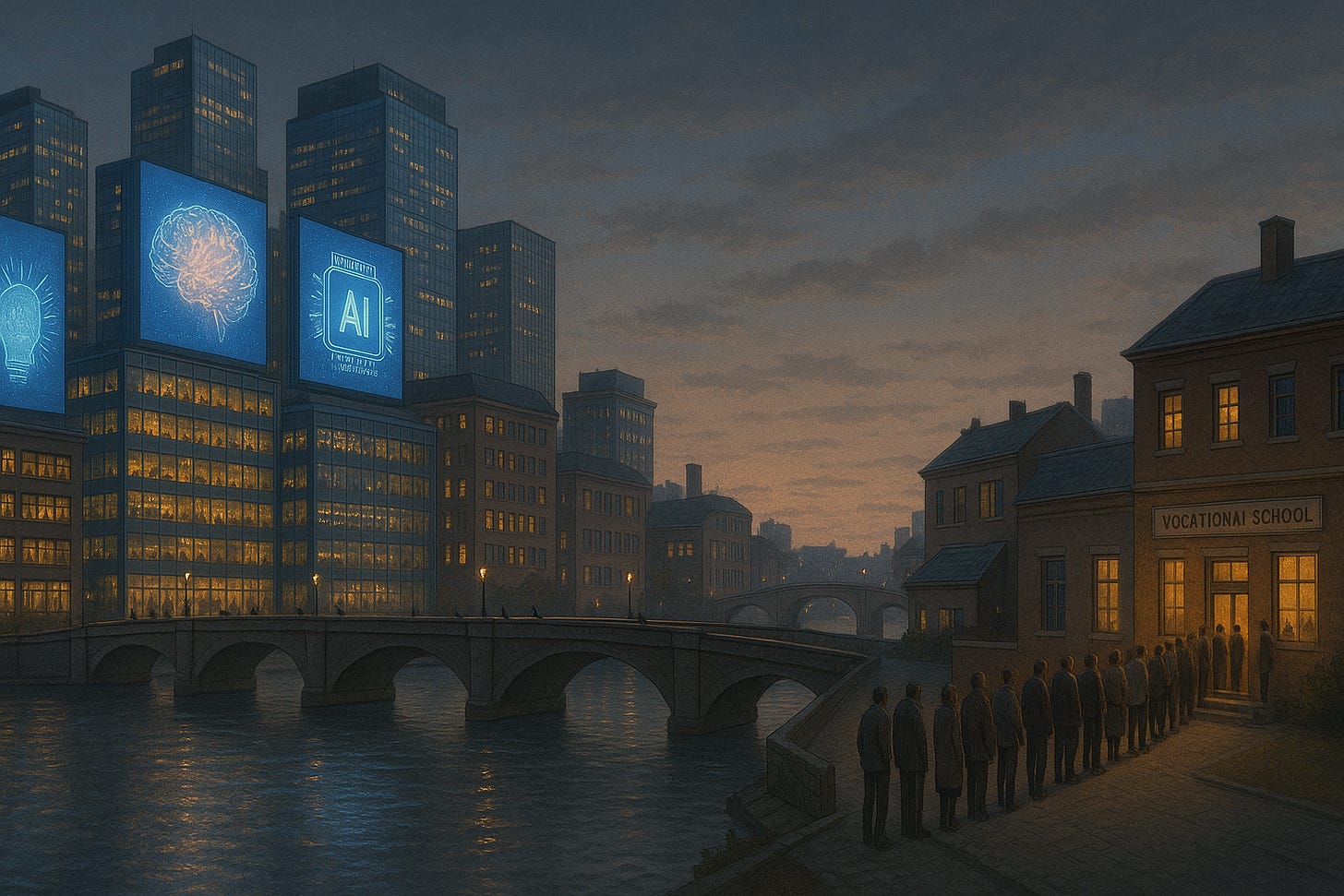

Who Gains From AI At Work, And Who Carries The Risk

AI, work, and inequality now sit together in the same sentence in many headlines and board rooms. The promise is higher productivity. The fear is a harsher divide between those who benefit and those who bear the cost.

This article looks at that tension through five lenses. Economic. Political. Sociological. Psychological. Leadership.

The goal is simple. Name the risk with honesty. Then describe what leaders, institutions, and citizens need to watch and do next.

A WORKDAY UNDER AI PRESSURE

Picture a weekday morning in early 2026. A project manager opens a laptop and a chat window shows a summary of meetings, draft emails, and code suggestions. A call center worker logs in and meets a new AI assistant that handles the first layer of customer questions. A teacher prepares lessons while a content generator offers quizzes and reading passages.

In each case, AI sits close to the core of daily work. Some workers feel relief. Routine tasks move faster. Others feel a knot in the stomach. Skills that once signaled security feel less rare. New tools keep arriving faster than training or policy.

Surveys show that this anxiety is not abstract. A 2025 Pew Research survey reports that about half of workers in the United States feel worried about future AI use in the workplace, and only a third express clear hope.[6] Public opinion data from Stanford’s 2024 AI Index show similar pessimism about AI and the wider job market.[7] A recent Harvard Youth Poll finds that 59 percent of young adults in the United States view AI as a threat to their job prospects, more than those who point to outsourcing.[8]

These responses frame the central questions.

CENTRAL QUESTIONS AND CORE TENSIONS

Two questions now shape the debate about AI, work, and social inequality.

Who gains from AI-driven productivity and who bears the risk of disruption and wage pressure

How do societies respond when most workers expect technology to reduce job security rather than raise living standards

Under those questions sit a few hard tensions.

Economic. Productivity growth versus wage and wealth concentration. AI systems raise output and profit potential. At the same time, many studies suggest that gains tend to favor capital owners and high skill workers unless policy and labor institutions adjust.

Political. Innovation speed versus democratic control. Governments face pressure to support AI investment for growth and competition, while citizens demand protection from job loss, surveillance, and bias.

Sociological. Opportunity versus exclusion. Regions, firms, and workers with digital skills and infrastructure move ahead faster. Others fall further behind. Existing gaps between urban and rural regions, and between rich and poor countries, risk expansion rather than closure.[4][5]

Psychological. Curiosity versus exhaustion. Many workers feel pressure to learn new tools while managing existing workloads. Surveys show a mix of interest, fear, and a sense of limited control.[6][7][8]

Leadership. Short-term gains versus long-term trust. Executives and public leaders face a choice. Pursue rapid efficiency gains without a clear social plan. Or share benefits through training, job redesign, wage policy, and safety nets.

These tensions shape the rest of the analysis.

WHAT THE NUMBERS SAY SO FAR

Global data now give a more concrete picture of AI and work.

The International Monetary Fund estimates that AI will affect around 40 percent of jobs worldwide, with exposure reaching about 60 percent of jobs in advanced economies.[1] The analysis warns that workers with higher education often gain from AI as a complement to their skills, while workers in routine roles face higher risk of displacement or wage pressure.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025 projects that AI and related technologies will displace around 92 million jobs by 2030 but also create around 170 million new roles.[2] These figures describe large churn rather than simple net loss. Workers must shift tasks, sectors, or skill levels at a scale that stresses existing systems for education and social protection.

OECD research shows that occupations with high exposure to AI cluster around certain tasks, such as information processing, pattern recognition, and routine analysis.[3] On average across member countries, roughly 28 percent of jobs sit in occupations at high risk of automation. Many of these jobs belong to younger workers and those with lower formal qualifications. Wage studies suggest that AI has started to narrow wage gaps within occupations, but large gaps between high and low wage occupations persist.[3]

A new UN Development Programme report warns that AI, if left unmanaged, may widen gaps between rich and poor states. Access to infrastructure, data, talent, and investment remains concentrated in a small set of countries and firms.[5]

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 lists technological power gaps and AI-driven information risks as medium term threats that interact with social instability and economic fragmentation.[9]

Taken together, these findings suggest a future shaped less by total job loss and more by unequal distribution of risk and reward.

ECONOMIC LENS: PRODUCTIVITY, JOB CHURN, AND WAGES

From an economic standpoint, AI functions as a general purpose technology. Output rises in sectors that integrate AI tools into workflows. Financial services, logistics, software, marketing, and professional services already show new forms of automation and augmentation.

Yet three concerns stand out.

First, productivity gains do not automatically translate into broad wage growth. Past automation waves often raised average incomes while leave many workers behind. Current research on AI and wages points in the same direction. Workers in high exposure roles with strong bargaining power and complementary skills tend to gain. Others face downward pressure or stagnation.[3]

Second, AI investment sits at the center of current market optimism. The OECD now flags the possibility of an AI-driven stock market bubble as a downside risk for the United States, with broader global effects if sharp corrections appear. Sharp swings in asset prices would raise uncertainty for firms and households and might slow job creation.

Third, job churn remains high even when total employment holds steady. Millions of roles transform in content or skill profile. Without serious reskilling and income support, disruption falls hardest on workers with the least margin. The WEF projections of 92 million jobs displaced and 170 million created by 2030 highlight the scale of this churn.[2]

The economic story, in short, points to strong gains for those with capital, data, and skills, and higher risk for those without these assets.

POLITICAL LENS: REGULATION, POWER, AND GLOBAL GAPS

AI also shifts political debates. Governments now face pressure to support domestic AI champions while also protecting citizens.

Regulatory efforts in the European Union, United States, China, and other regions attempt to address safety, transparency, and rights. Most of these frameworks arrive after broad deployment in the market. Workers already feel the impact while rules lag.

At the global level, AI investment and talent concentrate in a small group of countries. The recent UNDP analysis warns of a “next great divergence,” where advanced economies with AI capacity pull ahead, while many developing countries remain dependent on imported systems and standards.[5] This pattern echoes early phases of industrialization, with a risk of new forms of digital dependency.

Within countries, regions with strong universities and tech clusters adopt AI quickly. Rural regions and smaller cities lag behind. An OECD report on generative AI and local job markets predicts that AI will strengthen existing gaps between high productivity urban centers and other regions.[4]

Political trust sits on top of these structural gaps. If workers see AI regulations as weak or captured by industry, resentment toward both governments and major firms will likely grow.

SOCIOLOGICAL LENS: WHO GETS AI, WHO LIVES WITH AI

Sociological analysis focuses on how AI reshapes daily life for different groups.

Economic and education advantages have started to translate into AI advantages. The OECD-Cisco research on AI uptake finds strong divides across regions, age groups, and income levels. Younger, higher-income, and urban populations report higher exposure to AI tools and greater digital well-being than older or lower-income groups.[4]

In workplaces, new divides appear between “AI workers” and “non-AI workers.” A 2025 Pew study reports that about 21 percent of workers in the United States use AI at least sometimes in their job, up from 16 percent a year earlier.[6] These workers often sit in white collar roles. Many service and manual roles remain largely untouched by AI tools, at least for now.

Families feel differences as well. Households with good connectivity and devices gain access to AI tutors, health assistants, and productivity tools. Families without those resources stay with older systems and face higher barriers to entry. Global connectivity gaps reinforce this pattern, especially in regions where internet access remains limited.[5]

Existing social lines of race, class, and gender intersect with these digital divides. Without careful design, AI systems risk reinforcing bias in hiring, credit scoring, housing, and policing. Social trust then erodes further.

PSYCHOLOGICAL LENS: ANXIETY, MEANING, AND CONTROL

The psychological story sits in survey responses and in daily conversations.

The 2025 Pew workplace survey finds that 52 percent of workers feel worried about future AI use, while 36 percent feel hopeful and a third feel overwhelmed.[6] Stanford’s AI Index summarizes wider public sentiment in similar terms. Only a minority of respondents expect AI to improve the economy or the job market.[7]

Three themes emerge here.

First, loss of control. Many workers report that AI decisions feel opaque. People do not know which tasks will change next or how performance will be judged in an AI-rich environment.

Second, loss of meaning. Some worry that AI tools will hollow out the most satisfying parts of their work, such as creative problem solving or direct interaction, and leave a thin layer of oversight or prompt writing.

Third, fatigue. New tools arrive fast, with little time set aside for training or reflection. Workers must adapt while still meeting existing targets. That pace raises stress and lowers trust.

These emotional dynamics feed back into economic and political choices. Citizens who feel cornered by technology become more open to radical policy swings, conspiracy theories, or blanket resistance to innovation.

LEADERSHIP LENS: CHOICES THAT WILL SHAPE THE GAP

Leadership choices in the next few years will shape how AI affects inequality more than technical capabilities alone.

In firms, leaders face at least five decisions.

Speed of adoption. Rapid deployment without consultation can trigger backlash and loss of trust. Slower, staged adoption with worker input builds shared understanding.

Job design. Leaders can use AI to remove routine tasks and raise the skill content of roles, or to monitor workers more closely and lower autonomy.

Training and support. Serious, funded reskilling programs help workers move into new tasks and roles. Thin, symbolic training increases frustration.

Sharing of gains. Productivity growth can feed only into profits and share prices, or also into wages, shorter workweeks, or shared ownership.

Governance and voice. Clear policies around data use, monitoring, and contestability of automated decisions reduce fear and raise trust.

In governments, policy choices around education, worker protection, competition, and taxation will strongly influence how AI shapes inequality. Investments in broadband, public digital services, and skills support can lower gaps between regions and social groups.[1][3][5]

Leaders who treat AI as a narrow technical upgrade miss this wider field. AI now functions as a social choice about the shape of work and reward.

IMPLICATIONS FOR LEADERS AND COMMUNITIES

For leaders in firms, schools, hospitals, and public agencies, three implications stand out.

First, expect uneven impact across roles. Some workers will feel genuine support from AI tools. Others will feel threat. Leaders need clear communication and early involvement of those most affected.

Second, treat AI strategy as part of a wider social contract. Decisions about where to deploy AI and how to share gains will influence trust, retention, and community support.

Third, cooperate across sectors. No single firm or ministry can handle re-skilling, safety nets, and cross-border governance alone. Partnerships across business, labor, education, and civil society will matter.

PRACTICES FOR A FAIRER AI FUTURE

Several practical steps stand out for any institution concerned about AI, work, and inequality.

Run an AI exposure map for your workforce. Identify roles with high automation risk and roles where AI tends to augment rather than replace.

Design re-skilling programs that match real demand. Link training to clear job paths, not generic “future skills.”

Build worker voice into AI deployment. Use pilots, feedback channels, and transparent guidelines for AI use and data handling.

Set internal principles for sharing gains. Agree in advance how productivity growth from AI use will support wages, job quality, or shared ownership plans.

Track equity outcomes. Monitor how AI deployment affects different groups in terms of pay, promotion, and workload, and adjust policy when gaps widen.

These steps will not remove risk. They do shift the balance away from passive acceptance toward active shaping of AI in daily work.

A GUARDED HOPE

AI will alter many jobs and many labor markets. Current research supports that statement across global, regional, and firm-level studies.[1][2][3][5] The direction of inequality, though, remains a choice.

If gains concentrate in a few firms and regions, and if workers face disruption without support, social and political stress will rise. Global risk reports already note that trend.[9]

If leaders share benefits, invest in broad skills, and give workers real voice, AI has a chance to support higher productivity with more inclusive opportunity.

The next few years will show which path societies take. The decisions arrive now, not in some distant future.

SOURCES & FURTHER READING

[1] Georgieva, K. (2024). AI will transform the global economy. Let us make sure AI benefits humanity. International Monetary Fund.

[2] World Economic Forum. (2025). Future of Jobs Report 2025. World Economic Forum.

[3] OECD. (2024). Artificial intelligence and wage inequality. OECD AI Papers.

[4] OECD. (2024). Generative AI set to exacerbate regional divide in OECD countries. OECD Press Release.

[5] United Nations Development Programme. (2025). The next great divergence: Why AI may widen inequality between countries. UNDP.

[6] Pew Research Center. (2025). U.S. workers are more worried than hopeful about future AI use in the workplace. Pew Social & Demographic Trends.

[7] Stanford HAI. (2024). Public opinion in the 2024 AI Index Report. Stanford University.

[8] Harvard Institute of Politics. (2025). Harvard Youth Poll, Fall 2025. Harvard Kennedy School.

[9] World Economic Forum. (2025). Global Risks Report 2025. World Economic Forum.